Improvisation: A Way to Untake the World for GrantedWritten by Jeanne Lambin – This article is from AIM Issue 2 (released November 2023). Perhaps you have had this experience:Once you start noticing something and paying attention to it, you see it everywhere. This may be your experience with improvisation and the improvisational mindset: once you start engaging with it, you see it everywhere. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as the frequency illusion, occurs when the thing you’ve just noticed, experienced, or been told about suddenly crops up seemingly constantly. This phenomenon is thought to be due to our ability to pay “selective attention.” Selective attention is, just like it sounds, our ability to select and focus on a particular input while ignoring other things. Just because something captures our attention, does not mean that we actually attend to or are present for it. Our selective attention can fray over time. Indeed, when something is seemingly everywhere, it can be hard to pay sustained attention to the instances in which it occurs. We can take it for granted. In the haste and hustle of everyday life, we miss the tens of millions of improvisations, great and small, that whir and hum in the background of our lives. We can overlook one manifestations of the improvisational mindset: the urban landscape, aka our cities. Here’s a stunning fact: over 55% of the world’s population, about 4.22 billion people, live in urban areas. By 2050, the UN estimates, that number will grow to over 68%. If improvisation is everywhere, so too are cities. In recent years, I have come to think of cities, especially our older cities, as a very literal embodiment of accept and build (which could also be described as “Yes, and…”). The city provides the backdrop of so many of our lives. Those places, those spaces, provide the envelope in which we write and insert the letter of our lives. The city is much more than just a place or a space. It is a story. It is a scene partner in the co-creative process. As Winston Churchill once famously said, “We shape our buildings and afterward, our buildings shape us." I was shaped by the city. I was shaped by improvisation.

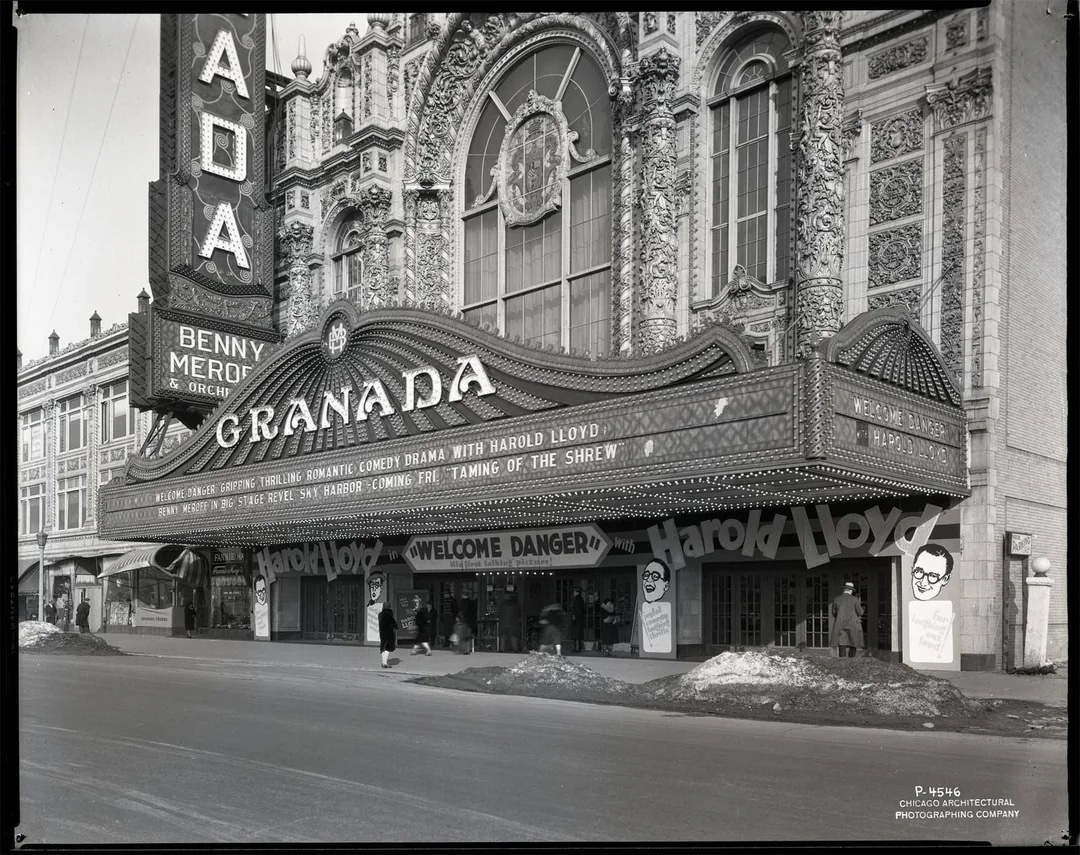

(Photo from Chicago Architectural Photographing Company)

Early Lessons in Letting GoI grew up in a city. I grew up in Chicago. I grew up in the same house that my dad grew up in, in the same neighborhood that my family had lived in for decades. The house became the final resting place for the assorted ephemera of many family members. Dishes from Aunt Mary, radio cabinets built by Uncle Lee, boxes of photos of people whose images remained, but whose names were forgotten. Lists, letters, legal documents, postcards, mass cards, card cards, and so on. I always felt an affinity for these items and the stories attached to them. These objects and stories were a proxy for people I would never meet. I was constantly pestering both of my parents for stories of these people that were no more. The past always felt very present, even if elements of it were rapidly disappearing. I grew up in the US, at the tail end of the first phase of the often-problematic program of urban renewal, funded by the US Federal Government (similar programs cropped up across the globe). In the US, as in many other places, this meant the dislocation and destruction of block after block of our visible past, earning it the moniker “urban removal”. By the time I arrived in this world, they were no longer clear-cutting vast swaths of Chicago, but demolishing the past was still a go-to option. I always found this great getting rid-of perplexing, baffling, and wasteful. I wanted to do something about it. One of the first buildings that I tried to “save” was the Granada Theater, an architectural confection, opened in 1926, at a time when movies were so grand, so splendid, and so unusual, that they required palaces in which to view them. Times changed, movie-watching habits changed, and the people who once populated the seats to full capacity disappeared. With the introduction of television, it was easy to take movies for granted. The collective selective attention had moved on. The Granada managed to stumble along, and it was still open, for a short window of my childhood. Enveloped in this cavernous space, dark save for the light of the screen and the exit lights, I watched Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and will forever remember Dave imploring Hal to open the pod bay doors, and the space inside the theater and the space on the screen becoming one. The theater closed shortly thereafter, and - after a few stilted efforts to revive it - thus began the slow slide into decline, because as much as we need buildings, buildings also need us. When we are not occupying them, their ecosystem of existence fails, giving way to rot and decay. By the time I was in high school, The Granada was threatened with demolition and replacement with an uninspired apartment block. I joined forces with the Save the Granada Theater committee, a rag-tag group of advocates to try to save it.

A Study in ContrastsIt was also at about this time that I enrolled in my first improv class at what was then ImprovOlympic (now iO) and started learning about the “rules,” or, as I like to call them, the building blocks of improvisation. I prefer this because it makes me think of being a kid with a trunk full of blocks, and how boundless and buoyant my young imagination was. Also embedded in the idea of a building block is the impulse to take something and transform it into something else. Accept and build. At the time, iO was housed in a characterful building with many previous lives. In a somewhat dingy classroom above a bar, I learned the ins and outs of attention, “Yes, and…”, letting go, and so much more. This was a stark contrast to what happened at City Hall, where, in asking that the City block the demolition, the Save the Granada Theater Committee heard that single, solitary, possibility-destroying word, no. After a protracted battle that spanned several years, the building was demolished. It was a painful and poignant lesson in the devastation of negation and a powerful lesson in letting go. Eventually, I returned to school to get my degree in historic preservation/heritage conservation, which can be broadly defined as preserving the past as a livable present for future generations. In historic preservation, there is, of course, the idea that you keep or preserve what is there. Then there is also the idea that if you are going to tear something down, you put up something better in its place. That did not happen with the Granada. It would take me a while to realize that historic preservation could be viewed as one of the ultimate expressions of “Yes, and…” or “accept and build.” To take what was there before and add to it. An accretive and collective effort to which we all contribute. When you look at an old building, a city, a skyline, you see the result of decades, if not centuries, of accepting and building. What if the university had said, “Yes, we will save the theater and transform it into something else.”? And I want to be absolutely clear: this is not a rallying cry to save everything, or that the past is all GREAT!!! It’s not. And I want to be absolutely clear: sometimes “no” is and should be a complete answer. “Yes, and…” or “accept and build” is no more the answer to everything, than saving everything is the answer to anything. In building cities, in building places, in building lives, there are those choices that, by their nature, remove so many other choices, so many possibilities. This was one of those. Things will get destroyed. Things will always get destroyed. That’s why we have the ability to let go. Because this is the Age of the Great Eradication, thus letting go becomes an essential skill to cope with the collective grief of so much erasure.

Accept and build...or notThis takes us back to the devastation of negation, those places where conflict, war, natural disasters, urban renewal, economic displacement, racism, rampant capitalism, and inequity have resulted in the erasure of places, and more importantly, the people and their stories that once populated them. No is a complete sentence. The idea of accepting and building, as applied to our places and spaces, is an invitation to be thoughtful, to be inclusive, and to be intentional. Our ability to pay selective and sustained attention can be a superpower. It could be said that intentionality is what makes improvisation applied. We can leverage our selective attention by attending to it, by being intentional. In cities, as in life, what we choose to accept and build on deserves careful consideration, a conscious and intentional counterpoint to what we intentionally overlook, erode, obfuscate, and destroy. In this Age of the Great Eradication, when so much is being destroyed, how can we be intentional about what we hold on to? How do we extend this beyond buildings and cities, to the world? How do we accept and build in this world? This world, this world, this world, so enmeshed in what some have described as the polycrisis, that even our crises have crises. The world is literally burning. How do you accept that? How do you build on that when it can be a relief to not pay attention to it, selective or otherwise? How do you let go to hang on? Perhaps you will have this experience: once you start noticing something, you can start accepting it, once you start accepting something you can start building something new from it Perhaps Applied Improvisation can bring ease to uncertainty and compassion when that ease is not available. Perhaps Applied Improvisation is a way to untake the world for granted.

About the Author: Jeanne LambinJeanne is a writer, facilitator, and storyteller based in Chicago. She is the founder of The Human Imagination Project which exists to help people connect to the magic of the ordinary, the extraordinary and everything in-between. She is the creator of Eleven Minutes To Mars, which helps people reimagine their relationship with time and attention in order to live with intention and the co-creator of The Quest: Improvisation for Transformation. (Read more from our magazine issues: click here to access our article database.) (Last Updated: Wednesday, January 28th, 2026) |