Mathematics, Teaching, and ImprovisationAn example of synergy for people who get annoyed by the word "synergy".Written by Doug Shaw – This article is from AIM Issue 1 (released December 2022). Author's Note:I’m taking all the math(s) out of this story – if you are curious about the math(s), there is a slightly longer version of this article available here: with the math presented gently for laypeople. This is a story about a single moment. A moment where I forgot my Applied Improvisation (AI) knowledge, and remembered it before it was too late. A wonderful experience, continuing through today, that would not have happened had I not remembered. We all have our moments – forgetting our AI knowledge. Sometimes we remember in time, sometimes we don’t. This is a story about one of mine when I remembered. I was teaching an international summer program for math-enthused students. We had spent a delightful few days talking about Hamiltonian graphs, Tough graphs, and Eulerian graphs. Worry not what these terms mean, it isn’t important to the story. I came to the climax of this part of the course – I had the students get into groups and prove that IF a graph was Hamiltonian, then it was Tough.

As we were summing up our discussion, and I was mentally rehearsing the introduction to our next topic, one student, Harris Spungen, asked if the converse of my statement was true – if every Tough graph was a Hamiltonian graph.

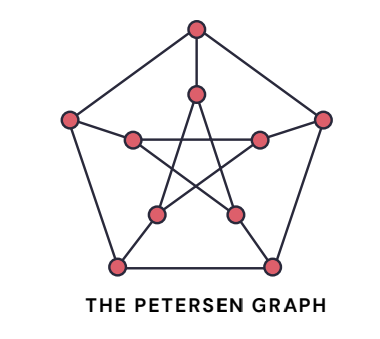

HARRIS’S FALSE CONJECTURE I had anticipated that question, and smoothly put this graph on the board: We verified that the Petersen graph was Tough and that it was not Hamiltonian. I was still on autopilot when Harris raised his hand, and told me he’d come up with a new conjecture:

I knew his new conjecture had to be false, because if it were true, I would have heard of it. I thought for minute, trying to come up with a quick counterexample. If you’ve ever taught, you know how long a minute is when you are standing at the board, thinking. I couldn’t come up with one, so I said, “I’ll get back to you on this tomorrow,” and went back to my lecture plan. After all, I’d been teaching for close to 30 years, and won teaching awards at four different universities, and I said, “I’ll get back to you on this tomorrow,” and went back to my lecture plan. I’d been going around the country giving my successful Improv for Educators workshops and I said, “I’ll get back to you on this tomorrow,” and went back to my lecture plan. I was teaching an ungraded course where I wanted the students to learn the thrill of mathematical discovery, and I said, “I’ll get back to you on this tomorrow,” and went back to my lecture plan. Fortunately, I thought... “Wait! What am I doing!” And I said, “Hey - you know what? Nothing else I had planned for today is as interesting as Harris’s conjecture. Let’s try to find a counterexample.” The extroverted students were at the chalkboard immediately, drawing and arguing. The more introverted ones had notebooks out, sketching and experimenting. Five minutes passed. Ten. A few of the ones whose mathematical experiences all involved immediate success were getting frustrated and mentally checking out. And a couple of the ones who had confidence problems were also checking out. When one group of three boys at the board called out, “I think we got it!”, I was in full-on Applied Improvisation mode, and made myself look busy and distracted. I asked the checked-out students for a favor - “Can you see if they are right?” And they were all too happy to be useful, running up to the picture, to see if it was a counterexample. It wasn’t – they showed it wasn’t. But by then someone else had a proposed counterexample, and off they went – the Harris Graph Verification Squad. Twenty minutes passed. Twenty five. When the HGV Squad were convinced that a counterexample worked, a teaching assistant and I would take a look, dashing hopes to the ground. Had Harris come up with a new condition after all? Nobody knew, not even me. And that is another lesson from Applied Improvisation in education. Uncertainty is okay. Chaos is okay. There’s a joy in not knowing. Just like on stage, when neither the audience nor the actors know how our heroes will escape from the cave guarded by bears. The teacher didn’t know if Harris was right, the students didn’t know if Harris was right, and Harris was having the time of his life trying to prove himself wrong. Thirty minutes. Ask a teacher friend how often you get a class of students completely involved in an activity for 30 minutes. Laughing, yelling, groups splitting and reforming. All looking for this holy grail, which I found myself calling a Harris Graph. While the HGV Squad ran from group to group, and the TAs were called in when they couldn’t break a potential graph, I was hanging back, because pedagogically I had decided – no, that is a lie – because I wanted to find a Harris graph, too. When working alone wasn’t doing it, I joined a group as an equal. Applied Improvisation lesson: Think about status. Think about status reversals. Finally, after about 45 minutes, one graph passed the HGV Squad‘s inspection, the TAs’ inspection, and my inspection. So I asked the entire class to help confirm. All 23 people in the room gathered around, students, teaching assistants, myself. Painstakingly checking Toughness, looking for Hamiltonicity by tracing cycles in the air with our fingers. I said to the class, “This graph is called a Harris Graph. We have proven they exist.” Every summer that I teach Graph Theory, I relate the tale of Harris, and we look for Harris graphs. Some groups find one, some don’t find any, some find several. One motivated student created and now curates a Harris Graph Zoo on the internet. Students are eager to come up with new Harris Graphs, knowing they will get their discoveries in the Zoo. So much has come from that day! I’ve published a paper about Harris Graphs, a student wrote code to check if a graph is a Harris graph, a later student created a nice interface for it, and a later student used that code to find all the Harris graphs of “order 10” or fewer. Another student asked me to mentor him on a Harris Graph research project, which helped him get into the university of his choice. Students have emailed me, asking me to help them understand mathematics papers as they independently researched the subject… all because I admitted I didn’t know the answer to a question. Harris graphs have inspired students to embrace their love of mathematics, to sometimes add the subject as a major or minor in college. Over 500 students have looked for Harris graphs. I cannot picture teaching Graph Theory without having a Harris Graph day. But what made it possible? Applied Improvisation. Let’s go back to the basic concepts that come up when we teach AI. Listening. Yes, Anding. Status. Inclusivity. Honesty and vulnerability. Persistence. Spontaneity. Think of your individual pet concept – that AI concept that you always include in every workshop you do – and think about how it was in the soup above. Mathematics is a large subject, Mathematics Education is a large subject, and this tale was an example of how Applied Improvisation can transform both of them.

About the Author: Doug ShawDoug Shaw is a mathematics professor who has won many awards for his teaching. His OK Zoomer workshop has been presented to over 10,000 instructors in over 12 countries. His Improv for Educators workshop has been helping educators throughout the United States. His favorite workshop to give is Collaborative Creativity, where the audience winds up writing, drawing, and telling stories together. (Read more from our magazine issues: click here to access our article database.) (Last Updated: Monday, February 9th, 2026) |